Spoiler alert: Those fish are scattering from YOUR noise, not your electronics

If you've been on social media lately, you've seen the arguments. "Fish scatter when I turn on my LiveScope!" "ActiveTarget spooks them!" "My buddy swears bass can hear his sonar pinging!"

Let me save you from another 47-comment Facebook thread: No, they absolutely cannot.

And I'm not just saying that as someone who runs LiveScope. The science is crystal clear—bass, walleye, pike, crappie, and every other freshwater gamefish you're chasing literally cannot detect the frequencies your sonar uses. Not through their ears, not through their lateral line, not through some mystical sixth sense.

But I get it. You've seen it happen. Fish were there, you fired up the electronics, and suddenly they vanished. So what's going on? Let's break this down three ways: the quick answer for when you're rigging at the ramp, the real explanation for why fish scatter, and then the hardcore science for everyone who needs peer-reviewed proof before they'll believe it.

Section 1: The Quick Answer (For When You're Rigging at the Ramp)

Question: Can bass hear my LiveScope/ActiveTarget/MEGA Live/2D sonar?

Answer: Nope. Not even close.

Here's the deal in plain English: Bass can hear sounds up to about 1,000 Hz (that's 1,000 vibrations per second). Your sonar? It operates at a MINIMUM of 50,000 Hz for traditional 2D sonar. LiveScope runs at 530,000 to 1,100,000 Hz. That's not a typo—that's five hundred to one thousand times higher than what bass can hear.

Asking if a bass can hear your LiveScope is like asking if you can hear a dog whistle that's been pitched 500 times higher. The answer isn't "probably not"—it's physically impossible. Their ears don't work that way. Period.

So Why Did Those Fish Disappear When I Turned On My Electronics?

Oh, they definitely spooked. But not from your sonar. They heard:

- Your boat engine or trolling motor - Bass hear 30-1,000 Hz perfectly. Your motor? Right in that sweet spot.

- That 3/4 oz weight you dropped on the deck - Yeah, that rattled through the hull like a dinner bell telling every bass in 50 feet to scatter.

- Your Spot-Lock firing up - Those prop pulses pushing water? Bass feel that with their lateral line from 20 feet away.

- You walking around the deck - Footsteps transmit through fiberglass hulls beautifully. Every step is a warning signal.

- Your boat's shadow - Bass have eyes. You're floating a 20-foot predator-shaped shadow over their heads.

The only reason we blame the electronics is because that's when we're WATCHING the fish. You turn on LiveScope, see the fish, then watch them swim away—and assume causation. But correlation isn't causation, folks. Those fish were already detecting your boat; you just finally had the technology to watch it happen in real-time.

The Bottom Line

Your sonar isn't spooking fish. You are. The good news? You were spooking them before LiveScope too—you just couldn't see it happening. Now you can see it, so you fish smarter: longer casts, stealthier approaches, quieter boat management.

If you want to stop here, great. Go catch fish. But if you want to understand WHY this is true and have ammunition for the next Facebook debate, keep reading.

Section 2: The Real Reason Fish Scatter (And It's Not Your Electronics)

Let's get technical, but not boring. If you're the type who actually reads your sonar manual instead of just turning it on and hoping for the best, this section is for you.

How Bass Actually Hear

Fish detect sound through three mechanisms, and understanding them is key to why sonar detection is impossible:

1. The Inner Ear (Otolith Organs)

Every fish has inner ears containing dense calcium carbonate stones called otoliths. When sound waves create particle motion in water, these stones move relative to surrounding tissue, triggering hair cells. This is how bass "hear" in the traditional sense. The problem? This system is mechanically limited to roughly 30-1,000 Hz in bass species.

Think of it like a guitar string—it has a natural resonance frequency based on its mass, length, and tension. You can't make a bass guitar string vibrate at frequencies meant for a violin. Same principle: bass otoliths physically cannot respond to ultrasonic frequencies.

2. The Lateral Line System

This is the one everyone brings up: "But what about the lateral line? Can't they feel the vibrations?"

The lateral line is a series of mechanoreceptors (neuromasts) running along a fish's body that detect water movement and pressure changes. It's incredibly sensitive—but only to 1-200 Hz, and effective range is measured in decimeters to meters, not tens of feet.

Your LiveScope at 530,000 Hz is operating at frequencies 2,650 times higher than the lateral line can detect. At 200 Hz, lateral line contribution to "hearing" already drops off significantly. By the time you hit even 1,000 Hz, it's essentially non-functional for sound detection.

3. Swim Bladder Coupling (Hearing Specialists Only)

Some fish—like channel catfish—have specialized connections (Weberian ossicles) between their swim bladder and inner ear. This extends their hearing range significantly. Channel cats can hear up to 5,000-6,000 Hz, making them "hearing specialists."

But bass? They're "hearing generalists." No Weberian ossicles. No swim bladder coupling. Just basic inner ear detection limited to 30-1,000 Hz.

Even if you're targeting channel catfish with their superior hearing, they max out at 6,000 Hz. Your traditional 2D sonar at 50,000 Hz is still 8 times higher than they can possibly detect.

Sonar Frequencies: A Reality Check

Let's put actual numbers to this, because the frequency gap is staggering:

Sonar Operating Frequencies vs. Bass Hearing Limits:

- Traditional 2D Sonar (50 kHz)

- Operating Frequency: 50,000 Hz

- Bass Hearing Limit: 1,000 Hz

- Frequency Gap: 50× higher than bass can hear

- Traditional 2D Sonar (200 kHz)

- Operating Frequency: 200,000 Hz

- Bass Hearing Limit: 1,000 Hz

- Frequency Gap: 200× higher than bass can hear

- Down/Side Imaging

- Operating Frequency: 455,000 - 1,200,000 Hz

- Bass Hearing Limit: 1,000 Hz

- Frequency Gap: 455-1,200× higher than bass can hear

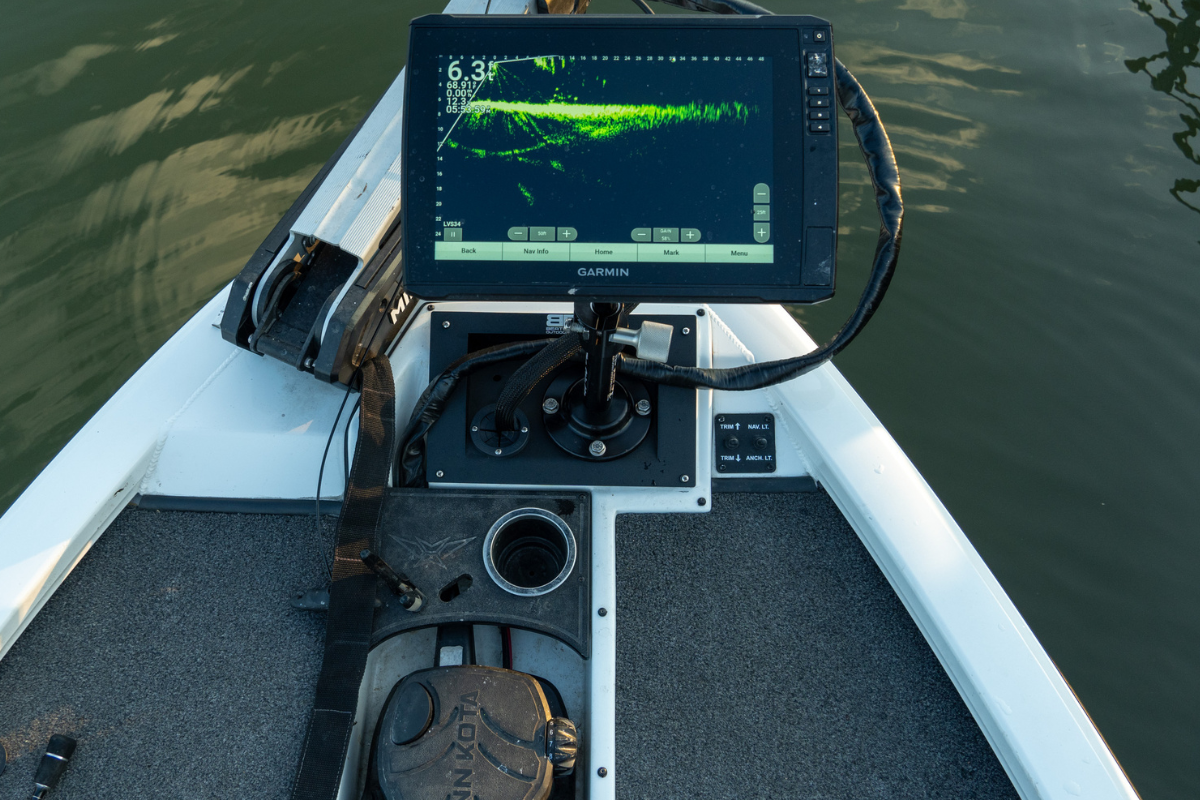

- Garmin LiveScope

- Operating Frequency: 530,000 - 1,100,000 Hz

- Bass Hearing Limit: 1,000 Hz

- Frequency Gap: 530-1,100× higher than bass can hear

- Humminbird MEGA Live

- Operating Frequency: ~1,200,000 Hz

- Bass Hearing Limit: 1,000 Hz

- Frequency Gap: 1,200× higher than bass can hear

Even the "lowest" frequency sonar—traditional 50 kHz used for deep water—operates at 50 times the frequency bass can hear. Forward-facing sonar? We're talking 500 to 1,000 times higher.

What About "Near-Field Effects" and Particle Motion?

Okay, here's where some people get technical and argue: "But fish detect particle motion, not sound pressure! Maybe they can feel it even if they can't hear it!"

Nice try, but no. Here's why:

Particle motion detection is still frequency-limited by the same mechanisms. The mass and stiffness of otolith organs determine their frequency response—just like how the mass and stiffness of your eardrum limits your hearing. You can't detect 100,000 Hz particle motion any more than you can detect 100,000 Hz sound pressure. The sensor (otolith or eardrum) simply can't vibrate that fast.

Near-field effects—where particle motion dominates over sound pressure—occur within approximately one wavelength of the sound source. At 800 kHz, that wavelength in water is about 1.9 millimeters. The near-field zone is smaller than the transducer itself. You're not creating detectable particle motion at the 20-50 foot ranges where you're watching fish on LiveScope.

The Elephant in the Boat: What Fish ACTUALLY Detect

Here's what's happening when those fish scatter, backed by actual research:

Engine/Trolling Motor Noise (10-1,000 Hz): This is right in the bass hearing sweet spot. Multiple studies have documented fish avoidance behavior around vessels. Your Minn Kota Ultrex on Spot-Lock? Every prop pulse is creating pressure waves bass can both hear AND feel with their lateral line.

Hull-Transmitted Noise: That tackle box you slid across the deck? That rod you dropped? Your footsteps? All of that transmits through fiberglass and aluminum hulls into the water at frequencies bass hear perfectly. In fact, bass have PEAK sensitivity around 100 Hz—exactly where impact noises and low-frequency vibrations occur.

Boat Shadow and Visual Detection: Bass have eyes. Good ones. Suspending a 20-foot shadow overhead while you idle around staring at your graph is like having a hawk circle over your head while you're trying to eat lunch. They know what boats mean: predators (anglers) or larger predators (ospreys and eagles that follow boats).

Cumulative Fishing Pressure: On heavily pressured lakes, bass learn to associate boats with danger. They don't need to hear your sonar—they learned last season that boats = hooks = bad news. This is learned behavior, not sonar detection.

Why The Myth Persists

Before LiveScope, you couldn't watch fish react to your boat in real-time. You'd pull up to a spot, start fishing, and either catch fish or not. You never saw them swimming away as you approached.

Now? You turn on forward-facing sonar and watch, in real-time, as fish move when you get close. You see them react to your boat positioning. You watch them relocate when you bump the trolling motor. And because you just turned on the electronics, your brain connects: "I turned it on, fish left, must be the sonar!"

It's classic correlation-without-causation. The sonar didn't spook them—it just gave you the technology to finally see what was always happening.

The One Exception (That Doesn't Apply to Bass)

Full disclosure: There IS one group of fish that can detect ultrasonic frequencies—American shad and some closely related species (alewives, some menhaden). They've evolved specialized inner ear structures that can detect up to 180,000 Hz. This likely evolved to detect echolocating dolphins that prey on them in marine environments.

But even these ultrasonic specialists can't detect the 265,000+ Hz of LiveScope XR or the 455,000+ Hz of imaging sonar. And more importantly: bass, walleye, pike, muskie, and crappie are not shad. They don't have this adaptation. At all.

My Opinion

The "sonar spooks fish" narrative is convenient for people who want to blame technology for their struggles. I get it—LiveScope changed the game. Tournament wins look different. Catching fish requires different skills. And if you haven't adapted, it's frustrating.

But blaming the sonar for spooking fish is just scientifically wrong. Fish are reacting to the same things they've always reacted to: your boat, your noise, your movement, your presence. The only difference is now you can SEE it happening.

Want to spook fewer fish? Here's what works:

- Longer casts (more important now than ever)

- Spot-Lock from farther away

- Minimize hull noise—no dropping weights, no stomping around

- Approach waypoints from deeper water when possible

- Use your big motor less; trolling motor more

- Fish early/late when boat traffic is lower

None of those involve turning off your electronics. Because your electronics aren't the problem.

If you need more convincing, Section 3 has all the peer-reviewed research. But if you're satisfied with the explanation, go fishing. Just keep the tackle box noise down.

Section 3: The Science (Peer-Reviewed Proof)

For those who want the academic receipts, here's the scientific foundation for everything stated above. This section contains specific citations, study methodologies, and data.

Fish Hearing Capabilities: Audiometric Studies

Bass Species Hearing Range

Holt & Johnston (2011) published audiograms for Micropterus species in Environmental Biology of Fishes(Volume 91, pages 121-126). Their research on redeye bass and Alabama bass demonstrated best hearing sensitivity at frequencies overlapping species-specific vocalizations—all below 200 Hz. The data showed a positive relationship between threshold and frequency, with sensitivity dropping dramatically above this range and functional hearing ceasing around 1,000 Hz.

Ladich & Fay (2013) conducted comprehensive auditory evoked potential audiometry research published in Reviews in Fish Biology and Fisheries (Volume 23, pages 317-364). Their work established that Centrarchidae (sunfish family, which includes bass) are hearing generalists with typical frequency ranges of 30-1,000 Hz and hearing thresholds of 90-120 dB re 1 μPa.

Comparative Freshwater Species

- Largemouth/Smallmouth Bass(Family: Centrarchidae)

- Hearing Range: 30-1,000 Hz

- Upper Limit: ~1,000 Hz

- Classification: Hearing Generalist

- Walleye(Family: Percidae)

- Hearing Range: 30-800 Hz

- Upper Limit: ~800 Hz

- Classification: Hearing Generalist

- Crappie(Family: Centrarchidae)

- Hearing Range: 30-800 Hz

- Upper Limit: ~800 Hz

- Classification: Hearing Generalist

- Channel Catfish(Family: Ictaluridae)

- Hearing Range: 50-6,000 Hz

- Upper Limit: 5,000-6,000 Hz

- Classification: Hearing Specialist

- Northern Pike(Family: Esocidae)

- Hearing Range: 30-800 Hz

- Upper Limit: ~1,000 Hz

- Classification: Hearing Generalist

Fay & Popper (1975) demonstrated the role of swim bladder coupling in extended hearing range. Their study in Journal of Experimental Biology (Volume 62, pages 379-387) showed that deflating a channel catfish swim bladder caused 30+ dB hearing loss above 200 Hz, confirming that Weberian ossicles connecting the swim bladder to the inner ear are essential for hearing specialist capabilities. Bass lack this anatomical feature.

Sonar Effects on Fish: Controlled Studies

High-Intensity Sonar Exposure

Popper et al. (2007) published results in Journal of the Acoustical Society of America (Volume 122, pages 623-635) from controlled exposure of largemouth bass, channel catfish, hybrid sunfish, rainbow trout, and yellow perch to high-intensity, low-frequency Navy sonar (100-500 Hz). Despite exposure at levels equivalent to those found 100 meters from active naval vessels—using frequencies within fish hearing range—researchers found:

- Zero mortality

- No permanent damage to auditory structures

- Only brief swimming bursts at sound onset

- Small, temporary threshold shifts that recovered quickly

- Fish appeared "healthy and active" post-exposure

This study is particularly significant because it used frequencies bass CAN hear (100-500 Hz) at high intensities, yet produced minimal effects. Ultrasonic frequencies they cannot hear would produce no effects whatsoever.

Ultrasonic Device Behavioral Studies

Getchell et al. (2022) exposed seven fish species to operating ultrasonic algae control devices in Oneida Lake, NY for 14 days. Results published in Lake and Reservoir Management definitively showed: "No avoidance behavior was detected in either shallow or deep water while the ultrasonic devices were operating." This directly contradicts anecdotal claims that fish flee from high-frequency devices.

Lateral Line System Capabilities and Limitations

Higgs et al. (2013) published comprehensive research in Journal of Experimental Biology (Volume 216, pages 1484-1490) examining the lateral line's contribution to acoustic detection. Key findings:

- Functional frequency range: 1-200 Hz maximum

- Effective detection range: decimeters to meters from source

- At 200 Hz, lateral line contribution already drops significantly

- No evidence of detection capability above 200 Hz under any conditions

Bleckmann (2023) in Journal of the Acoustical Society of America (Volume 154, pages 1274-1288) confirmed that lateral line neuromasts respond exclusively to low-frequency water movements and cannot function as ultrasonic detectors.

Ultrasonic Detection: The Clupeid Exception

Mann et al. (1997, 1998, 2001) discovered that American shad (Alosa sapidissima) and some related Alosinae subfamily species possess specialized ultrasonic detection:

- Mann et al. (1997): "A clupeid fish can detect ultrasound" in Nature Volume 389, page 341

- Mann et al. (1998): "Detection of ultrasonic tones by the American shad" in Journal of the Acoustical Society of America Volume 104, pages 562-568

- Mann et al. (2001): "Ultrasound detection by clupeiform fishes" in Journal of the Acoustical Society of America Volume 109, pages 3048-3054

Findings: American shad can detect up to 180 kHz, likely an evolutionary adaptation to detect echolocating dolphin predators. However:

- This capability is limited to Alosinae subfamily (shads, alewives, some menhaden)

- Even within clupeids, Pacific herring cannot hear above 5 kHz

- Bass, walleye, pike, crappie, and muskie lack the specialized utricle anatomy enabling this capability

- Even 180 kHz detection falls short of 265+ kHz forward-facing sonar and 455+ kHz imaging sonar frequencies

Sound Detection Mechanisms: Particle Motion vs. Sound Pressure

Popper & Hawkins (2019) published "An overview of fish bioacoustics and impacts of anthropogenic sounds on fishes" in Journal of Fish Biology (Volume 94, pages 692-713). This comprehensive review established that:

- All fish detect particle motion as their primary hearing mode

- Particle motion detection is frequency-limited by otolith organ mechanics

- Mass and stiffness of otoliths determine frequency response capability

- No evidence exists for particle motion detection outside established frequency ranges

Comprehensive review by Ladich & Schulz-Mirbach (2016) in Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution examined diversity in fish auditory systems, confirming that hearing generalists (including bass) are mechanically constrained to low frequencies regardless of whether detecting particle motion or sound pressure.

Recreational Sonar Technical Specifications

Forward-Facing Sonar

- Garmin LiveScope/LiveScope Plus: 530-1,100 kHz CHIRP, 500W transmit power

- Garmin LiveScope XR: 265-550 kHz CHIRP for extended range

- Lowrance ActiveTarget: Proprietary CHIRP frequency (manufacturer does not disclose exact range)

- Humminbird MEGA Live: ~1,200 kHz based on MEGA Imaging technology

Imaging Sonar

- Lowrance StructureScan/DownScan: 455 kHz, 800 kHz, 1.2 MHz options

- Garmin ClearVü/SideVü: 400-500 kHz (CHIRP 455), 740-900 kHz (CHIRP 800), 940-1,100 kHz (UHD)

- Humminbird MEGA Imaging: 1,150-1,275 kHz CHIRP

Traditional 2D Sonar

- Single Frequency: 50 kHz, 83 kHz, 200 kHz

- CHIRP Low: 25-80 kHz

- CHIRP Medium: 80-160 kHz

- CHIRP High: 150-240 kHz

All frequencies exceed fish hearing capabilities by factors of 25× to 1,200×.

Vessel Noise and Fish Avoidance Behavior

Scholik & Yan (2001, 2002) documented measurable hearing threshold shifts in fathead minnows exposed to boat motor noise. Their research in Environmental Biology of Fishes established that outboard motor noise (peak frequencies 100-1,000 Hz) falls directly within fish hearing sensitivity ranges and creates documented avoidance behaviors.

Purser & Radford (2011) in Biology Letters demonstrated that boat noise impairs reef fish recruitment and communication at ranges up to several hundred meters, with effects concentrated in the 50-800 Hz range—exactly matching bass hearing sensitivity.

Conclusion from Peer-Reviewed Literature

The scientific consensus is unambiguous:

- Largemouth bass, smallmouth bass, walleye, crappie, pike, and muskie have maximum hearing capabilities of approximately 800-1,000 Hz

- All recreational fishing sonar operates at minimum frequencies of 25,000-50,000 Hz, with forward-facing and imaging sonar operating at 265,000-1,200,000 Hz

- This represents a frequency gap of 25× to 1,200× above fish hearing limits

- Lateral line detection is limited to 1-200 Hz with effective range measured in decimeters to meters

- Controlled studies show no avoidance behavior when fish are exposed to ultrasonic frequencies

- Fish avoidance of boats is attributed to engine/motor noise (10-1,000 Hz), hull-transmitted vibrations, visual detection, and learned behavior from fishing pressure

Claims that bass can hear or are spooked by sonar are not supported by any peer-reviewed research. The frequencies are physically incompatible with fish auditory and mechanosensory capabilities.

Additional Scientific Resources

Primary Research Citations:

- Fay, R.R. & Popper, A.N. (1975). Modes of stimulation of the teleost ear. Journal of Experimental Biology62:379-387

- Higgs, D.M. et al. (2013). The contribution of the lateral line to 'hearing' in fish. Journal of Experimental Biology 216:1484-1490

- Holt, D.E. & Johnston, C.E. (2011). Hearing sensitivity in two black bass species. Environmental Biology of Fishes 91:121-126

- Ladich, F. & Fay, R.R. (2013). Auditory evoked potential audiometry in fish. Reviews in Fish Biology and Fisheries 23:317-364

- Mann, D.A. et al. (1997). A clupeid fish can detect ultrasound. Nature 389:341

- Popper, A.N. et al. (2007). Effects of exposure to seismic airgun use on hearing of three fish species. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 122:623-635

- Popper, A.N. & Hawkins, A.D. (2019). An overview of fish bioacoustics and impacts of anthropogenic sounds on fishes. Journal of Fish Biology 94:692-713

Online Resources:

- International Game Fish Association: "Hearing in the Underwater World" - https://igfa.org/2021/02/26/hearing-in-the-underwater-world/

- GeoExpro: "Marine Seismic Sources Part VIII: Fish Hear A Great Deal" - https://geoexpro.com/marine-seismic-sources-part-viii-fish-hear-a-great-deal/

- Phys.org: "Study Shows Sonar Did Not Harm Fish" - https://phys.org/news/2007-07-sonar-fish.html

Final Thoughts

The next time someone on social media claims their LiveScope is spooking fish, you've got three options:

- Send them Section 1 if they just need the quick answer

- Send them Section 2 if they want to understand the mechanics

- Send them Section 3 if they need peer-reviewed proof before they'll believe it

Better yet, send them this entire article and settle the debate once and for all.

Your sonar isn't spooking fish. Your boat, your noise, and your presence are—same as they always have been. The difference is now you can watch it happen in real-time on a screen instead of wondering why you're not getting bites.

Fish smarter, not louder. And keep that tackle box from sliding across the deck.

Tight lines,BassFishingTips.net